A momentous guessing game of three questions has entered its second week. When and how will Hezbollah and Iran retaliate for the assassinations of Hezbollah military leader Fuad Shukr in Beirut on July 30 and Hamas political chief Ismail Haniyeh in Tehran on July 31? How will Israel respond to what will presumably be a coordinated Hezbollah-Iranian attack? Most alarming, will these actions tip the Middle East into the full-scale regional war feared ever since Hamas’s October 7 attack and the start of the massive Israeli military campaign in Gaza?

The post-October 7 escalatory cycle of violence between Israel and Hezbollah inevitably provokes comparisons to the 34-day Israel-Hezbollah war of 2006, when I served as U.S. ambassador to Lebanon. But the 2006 example, while devastating (with widespread destruction and displacement, and about 1,200 Lebanese and 165 Israelis killed), is grossly inadequate to describe the current peril. Both the Israelis and Hezbollah have studied and learned from the 2006 war, on the assumption that another war is inevitable and that each side must be better prepared. Unlike the situation with Hamas before October 7, Israel has fully understood the potential lethality of Hezbollah’s weaponry and methods and has for years focused on disrupting and countering the weapons flows from Iran via Syria to Hezbollah.

Hezbollah is also stronger militarily and politically than in 2006. As has been widely reported, its tunnel network has expanded, and its arsenals, dispersed across Lebanon, are exponentially larger, with more numerous and more advanced weaponry that can reach virtually all of Israel. Syria’s civil war has, since 2012, provided on-the-ground training for Hezbollah fighters, who, battled-experienced, now resemble a regular army.

Politically, in July 2006, many Lebanese reacted in outrage to Hezbollah’s unprovoked infiltration into Israel and the abduction of two Israeli soldiers, actions that triggered an instantaneous war that destroyed Lebanese hopes for a peaceful, tourist-filled, lucrative summer. Whether sincere or a postwar attempt at public relations, Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah sensed the imperative to apologize for initiating the war. Now, given Israel’s 10-month unrelenting military campaign in Gaza, the ongoing low-scale war between Israel and Hezbollah, and the assassination of Hezbollah and Iranian leaders, even those Lebanese who hope that a full-scale war never materializes may not blame Hezbollah to the same degree as they did in 2006, if war does break out. In addition, Hezbollah’s grip on Lebanese political life is tighter than ever.

Unlike today, July 2006 offered no waiting time for civilians to relocate. With Beirut’s airport bombed and its air and maritime space blockaded from the war’s first day, approximately 15,000 American citizens were evacuated in what was then one of the largest U.S. government non-combatant evacuations in history. This year, with increasing urgency, foreign embassies in Beirut have advocated that their citizens depart Lebanon by commercial means while still available.

Most seriously, the broader context has changed since 2006. The conditions that inhibited the 2006 Israel-Hezbollah war from escalating into a regional conflagration have evaporated as Iran’s “axis of resistance” has solidified. While Hamas’s and Hezbollah’s tactics in 2006 might have been similar, they did not claim to be pursuing coordinated agendas. In January 2006, Hamas won the Palestinian legislative elections in Gaza and dragged the territory to war with its June 25, 2006, kidnapping of Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit. But this was not linked to Hezbollah’s abductions that triggered the July 2006 war in Lebanon. Israel’s military response to these separate kidnappings did not have the deadly reinforcing logic and spiraling of today’s violence.

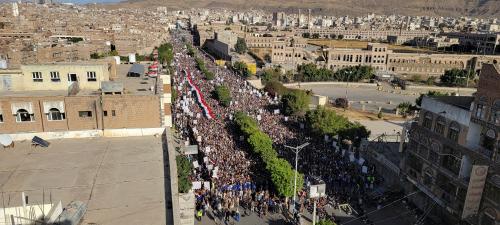

As for Iran, while Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei and President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad barked out a steady drumbeat of vile statements about Israel and Jews in 2006, Iran’s anti-Israel bite was exercised through proxies that did not have the same sophistication, lethality, and geographic scope of Iran’s proxies today. Yemen’s Houthis had been engaged in a series of military conflicts with Yemen’s government under then-President Ali Abdullah Saleh, who in the spring of 2006 offered amnesty to some Houthi fighters before skirmishes resumed the following year. Any relationship between Iran and the Houthis in 2006 threatened neither global shipping nor Tel Aviv. In Iraq, 2006 was a particularly bloody year between Shia and Sunni militias, with both focused on domestic slaughter, not drone attacks on Israel. In Damascus, Bashar al-Assad was licking his wounds from Syria’s humiliating expulsion from Lebanon the previous year after being blamed for the assassination of former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik Hariri, limiting Assad’s appetite for adventures that could further damage Syrian prestige.

In 2006, solidarity with the Palestinians from any of these groups was confined mostly to rhetorical support. Today, any or all could participate in turning the current situation into a full-scale war. For their own reasons, Hezbollah, Iran, and Israel each probably hopes to calibrate its military actions to avoid a full-scale war. But escalatory cycles are hard to control in situations such as today’s, where no precedents exist and previous unwritten rules of the game—such as tit-for-tat geographically limited and low-casualty strikes between Hezbollah and Israel—have been discarded. Miscalculations that accelerate escalatory violence can occur: the July 27 strike on Majdal Shams in the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights was presumably intended for a military target, not a Druze soccer field where 12 children and teenagers were slaughtered.

The United States, however, is far better prepared to defend its interests than in 2006. The Hezbollah abductions that provoked the 2006 war caught the U.S. government by surprise, and it took over a week before military assets were available to assist in the evacuation and to protect U.S. personnel. As we witnessed in April, the United States has deployed its military and its diplomacy to build an effective coalition to help reduce the impact of attacks from Iran and its allies, partners, and proxies.

Compared to 2006, the entire region is in dangerous, uncharted territory. A cease-fire/hostage release/humanitarian surge agreement for the Gaza Strip would facilitate urgent diplomacy from the Biden administration and others to de-escalate current tensions. But the clock to war and the clock to a cease-fire do not seem to be synchronized.

Commentary

Echoes of 2006: Israel, Hezbollah, and the potential for regional war

August 9, 2024