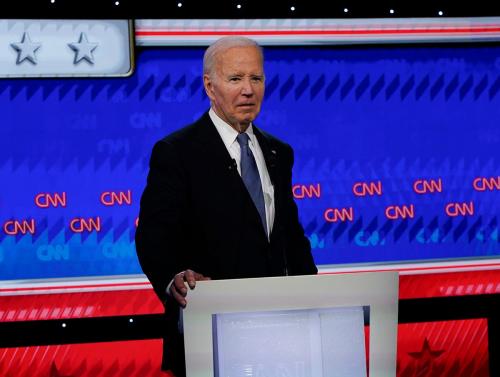

On Sunday, July 21st, President Joe Biden announced that he would no longer seek the Democratic Party’s nomination for president in the election against Donald Trump this November. He then endorsed Vice President Kamala Harris for the nomination. To talk about this momentous development in the 2024 presidential election, Brookings Senior Fellow E.J. Dionne joins The Current.

Transcript

[music]

DEWS: You’re listening to The Current, part of the Brookings Podcast Network, found online at Brookings dot edu slash podcasts. I’m Fred Dews.

On Sunday, July 21st, President Joe Biden announced that he would no longer seek the Democratic Party’s nomination for president in the election against Donald Trump this November. Writing that, quote, “while it has been my intention to seek reelection, I believe it is in the best interest of my party and the country for me to stand down and to focus solely on fulfilling my duties as president for the remainder of my term,” unquote. He then endorsed Vice President Kamala Harris for the nomination.

Here to talk about this momentous development in the 2024 presidential election is E.J. Dionne, the W. Averell Harriman Chair and senior fellow in Governance Studies here at Brookings. He’s also a syndicated columnist for The Washington Post and university professor in the foundations of democracy and culture at my alma mater, Georgetown University.

And let me add that leading up to the U.S. elections in November, Brookings aims to bring public attention to consequential policy issues confronting voters and policymakers. You can find explainers, policy briefs, other podcasts, and more. Please sign up for the weekly email by going to Brookings dot edu slash Election 24.

E.J., welcome to The Current.

DIONNE: A joy to be with you. Thank you. And Hoya Saxa about your great university, if I may.

DEWS: Hoya Saxa, indeed you may. Well, E.J., you’ve been a keen observer and commentator on American politics for decades. Can you offer a personal reflection of your feelings on this development?

DIONNE: You know, it’s it’s funny that you ask that for two reasons. One is, that I joke with people that I am been around so long that I covered Joe Biden when he was the new generation candidate. That would be way back in 1987. And, if you look back there, he gave some great speeches, in fact, about the need to pass power to a new generation. And, you know, from that experience, I’ve developed a real fondness for Joe Biden over the years. Partly, you know, I grew up in a mill town called Fall River, Massachusetts. He grew up in a mill town called Scranton, Pennsylvania. And I have a lot of sympathy and maybe even empathy for the broad worldview Biden has.

So, I felt that way about him not, you know, not always uncritical. I’ve reported, I reported over the years on things that weren’t necessarily flattering to Biden. But I find him a person, who is very easy to relate to and whom I think his heart is broadly in the right place.

At the same time, on Sunday, I had a column go up in the Post at 7:00 that morning, hours before he withdrew, essentially saying that he had to withdraw, that the Democrats, thanks to former President Trump’s long, rambling 92-minute speech, which didn’t do what his advisors said he would do—focus on the personal story of the shooting, which all, you know, all Americans were horrified about that shooting—and that he was going to talk about national unity. He didn’t do that. So that gave an opening to Democrats.

But I felt and still feel in retrospect that Joe Biden after the debate—and it wasn’t just the debate, it was the larger doubts that really triggered among people who had thought that even though he was 81, he could make it all the way through not only the campaign, but a second term—I thought that that made it very hard for a lot of voters to conclude that. And so, I had this column up and then I happened to be at a party celebrating one of my nieces and up on the screen in the, in the bar in the restaurant was the Biden story. And so, I quickly had to change that column.

And so, my reaction was that while I felt badly for Biden, I thought he had done what he had to do. I really think that had he pursued this race, and had he lost as a result, it would have destroyed what was otherwise a very significant legacy, a really significant legacy as president. So, I felt in the end he did what he had to do. And you saw that in the response across the Democratic Party. And not just in the Democratic Party to, you know, his decision to do that, I think it was necessary to open the race up again.

DEWS: And so, you talk about legacy. Can you help us, E.J., situate this event in historical terms? A lot of people are looking at 1968 as the last time a sitting president who was expected to run for reelection, bowed out of the race. Lyndon Johnson, I think it was in March of ‘68, opening up the field to other candidates. And then another similarity with this year, although probably a superficial one, is that the 1968 Democratic National Convention was held in Chicago. Can you talk about your sense of the historic proportions of this and the historic context of this?

DIONNE: Yeah, a lot of people are talking about ‘68 in, in, in relationship to this. I think this is actually quite different. In one sense, we’ve never really seen anything like this because Lyndon Johnson dropped out after one primary where, although he won the New Hampshire primary, technically it was such a close race against Eugene McCarthy, the anti-war Democrat who challenged him on the basis of the Vietnam War, that he decided to end his candidacy right there. And then you had a whole series of primary fights between Gene McCarthy, Robert Kennedy, who, you know, very sadly, it was a tragic event, he won the California primary at the end of that process in June and then got shot.

In the meantime, Johnson’s vice president, which is also drawing comparisons here, Hubert Humphrey, while he didn’t really fight the primaries, became the nominee because the process wasn’t then based in primaries as it is now.

In this case, you had Biden dropping out after he had won all the primaries, I guess, except for American Samoa. Kind of flukey loss. But he had won all all the other primaries. And so, this was dropping out in a very, very different circumstance.

I also think that the division in the Democratic Party in 1968 were so, so, so much deeper than they are now. In fact, right now, the Democratic Party, because it sees its mission as stopping former President Trump from taking office again, I think is surprisingly united. It was at this point only Biden’s candidacy that was starting, which had been unifying a month and a half ago, was starting to be divisive.

So, I think this is an event all by itself that defies comparison with any other event that may be a little like it. But I don’t think it’s on par with anything I can think of.

DEWS: So, I think we’re about four weeks away from the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. And President Biden has said that he supports Vice President Kamala Harris for the ticket. She’s starting to round up support from state party chairs, from delegates themselves, endorsements from leading elected Democrats around the country. But there was a moment right after the debate in June that kind of kicked off this process where some people said that there should be some kind of a fast primary and mini primary held in perhaps in the media amongst Vice President Harris and some other names that have cropped up. So, looking ahead, four weeks to go until the nomination of the party’s candidate, do you think that maybe they should have tried more for that kind of, in-the-media at least, an open, mini, fast primary or, you know, the way that the process is unfolding now, how does it seem to you?

DIONNE: Well, to have a race, you need lots of people to show up in the starting blocks. And what happened in the last 24 hours from when we speak, maybe a little more than that, is that all of the potential candidates, all of the strong potential challengers to Kamala Harris decided not to make the race. Governor Gretchen Whitmer of Michigan decided, no, I’m not making this race. And she endorsed Kamala Harris. Governor Josh Shapiro of Pennsylvania, another potentially strong candidate someday like Whitmer, decided, no, I’m not making this race now. And he endorsed Kamala Harris.

So, you were left in a situation where not only did lots of people in the party, lots of members of Congress, lots of delegates, lots of state parties endorsed Kamala Harris right away. You had virtually all her strong potential opponents—Gavin Newsom, governor of California, is another one—who said, no, we support Kamala Harris. So, there wasn’t an opportunity to have that race because the people who might have made it chose not to do it.

Now, I think Harris early, right at the beginning when she, you know, essentially accepted Joe Biden’s endorsement and said she wanted the nomination, said she was prepared to be tested. And I think that at least she sent that signal, which was useful.

I think in the end, it’s hard for it to be seen as an unfair process, given that a lot of the potential opponents just decided not to run. And that, you know, I’ve always been mixed on this, I thought that the party would ultimately turn to Kamala Harris, and there were a lot of reasons for doing that. I thought a process that looked fair to voters would be good. But I never had a romantic view of what the competition could look like. Inter-party competition can cause a lot of division, and Democrats seem particularly good at that, I’ve noticed that over the years.

And so, while it would have been interesting and certainly would have drawn a lot of attention, I think when you saw that flood of endorsements, what you saw were a lot of political leaders, a lot of people who are going to be on the ballot with the presidential candidates say, no, we’re better off to unite quickly. And she will be ratified by a democratic process. It just doesn’t look at the moment like she’ll have any real, any strong opposition.

Somebody could still turn up. I’ve decided in this election that anybody saying anything on a podcast or in print always has to be open to the idea that about ten minutes after the light goes out, something odd is going to happen. It doesn’t look like it, but you never know.

DEWS: Well, part of the ratification process, as I understand it, is that the delegates that emerged from the primary process for the Biden-Harris ticket are still going to go to the convention in Chicago, and they will then nominate her. So, it will still feel like, at that point at least, a regular nomination process. And then she’ll pick her VP. Is that right?

DIONNE: Well, they’re probably going to do a, they’re going to have an early roll call because there is some concern in a few states, Republican states, that if they don’t meet a certain date target, those states might not list the Democratic ticket on the ballot. And so, I don’t think that’s likely to happen now. Ohio had a law that made it difficult. They repealed that. They they changed that law.

But I think there is probably going to be an early, an early roll call, which will then turn the Democratic convention into what the Republican convention was, which is essentially a nightly TV commercial for the party and the party’s, candidate. But yes, there will be an official democratic process one way or the other, whether it’s early or in Chicago, ratifying her nomination and the person she picks to be her vice president, which is obviously the first really big decision that she has to make.

DEWS: So, let’s stick on the political tactics now for a moment. Some Republicans are already arguing that if Joe Biden’s incapable of running for president, he’s incapable of being president and should step down. We’ve also seen J.D. Vance, the GOP’s vice presidential nominee, saying that Kamala Harris has essentially lied about Joe Biden’s condition. What do you make about what you’ve seen so far in terms of the Republican Party’s and the Trump campaign’s reaction to these events?

DIONNE: Well, I’m not surprised that they’re doing either of those things. The they had organized an entire campaign to run against Joe Biden. And so, this came, I mean, by the time it happened, you know, they had begun to anticipate the possibility of that. But they wanted to run against Joe Biden. They made it very clear that they wanted to run against Joe Biden. And that is one of the things that people urging Biden to get out of the race pointed out to him very early on. Tom Friedman said, you know, the best path for a politician is not to do what the enemy wants him to do. And it was about Republicans wanting to run against Biden. So, they are doing what they can here to cause some mischief—opposition parties do that.

I think on the first, the notion that Joe Biden should step down, I don’t think that’s going to go anywhere. I don’t think the voters want him to step down early. The idea that perhaps he’d have a problem at the end of a second four-year term, or that he might not want to run a campaign between now and November is not the same as saying he’s incapable of being president. He has been, by many measures, I would argue, even though the Republicans would obviously disagree with this, there are a lot of successes he’s had as president, and I think that that they’ll keep saying that they may try to make some effort to push him out. I don’t think that’s going to go anywhere.

I think the second question that they’re asking, you know, essentially, they want a what did Kamala Harris know and when did she know it about his condition? I think that’s an interesting question in general. I’ll tell you what my impression is from talking to a lot of people. I hadn’t seen, I haven’t seen the president myself in a while. But I did talk over the last few weeks to a lot of members of Congress and, like, who saw him. There’s really a lot of talk that that he may have deteriorated a fair amount in his condition over the last 4 to 6 months. And I think one of the questions that, you know, it may take historians to answer, I’m sure a lot of journalists are trying to answer it now is, you know, what was his condition, say, last year at the end of last year? What was it in January? And, you know, where did that debate performance come from? And I don’t think we know the answer to that, yet.

And I think there were enough times when Joe Biden was certainly coherent and strong. He was very strong in his State of the Union speech, not only from what he read on the teleprompter, but in interacting with a little bit of heckling that he got from the audience. A lot of us—I certainly am in that camp—thought, okay, he’s ready to do this. And that was in March, if memory serves.

And, you know, so I think, I think there are a lot of ways she can respond to that, but it’s a it’s a legitimate enough question to ask for of everybody who was around Biden.

DEWS: I’ll just observe that if, President Biden stepped out of the Oval Office, that would make Kamala Harris the next president. And so, then Donald Trump would be running against President Harris as opposed to Vice President Harris.

DIONNE: Correct. That’s right.

DEWS: And just to bring up one more strategic or tactical question, a lot of observers I’ve read are saying that Republican strategy was built solely on the idea that they were going to run against Joe Biden, and they were going to make him make the case against his age and his competency. Now that he’s out, the Republican Party has now the distinction of nominating the oldest person to ever run for president in Donald Trump.

DIONNE: Correct. And, you know, Kamala Harris jumping in the race flips the age issue altogether. And you’ve already seen indications that Democrats are very eager to make this campaign about the future versus the past. I think there’s going to be a lot of requests of the media that I think legitimately covered the Biden story and his aging now pay at least as much attention to the way Donald Trump speaks and where his lapses are and where you might say is Donald Trump getting old? And I think you’re going to see the Democrats use that as an issue.

In terms of running against Biden, they’re going to try to link Kamala Harris to every problem they want to associate with the Biden administration. I mean, there is plenty of, there’s plenty of video of people referring to it as the Biden-Harris administration. And those are words that are going to come out of Republican advertising shops and their candidates between now and the election.

I think it’s very intriguing, to and I don’t personally know either what the right answer to this question is or how they’ll do it. Harris has on the one hand some opportunity to distance herself a little bit from Biden because she wasn’t president. And she can thus be a bit of a candidate for change. On the other hand, there are a lot of things Biden did that are popular and that she supports, and that Democrats support and are proud of that she wants to talk about.

So, I think it’s a it’s, I think it’s going to be a very interesting set of strategic choices that Harris will be making about exactly how she can’t and shouldn’t disassociate herself from the last four years altogether. I think she’s going to be very gracious to Joe Biden. But can she create a little bit of distance that’s useful to her? We’re going to see whether she can pull that off. And it won’t be it won’t be easy. It will take a lot of skill.

DEWS: I heard another Brookings scholar say this earlier, that removing this age and competency question from the campaign elevates the policy questions. And you were just talking about how the Harris-Biden administration’s record will now be, a focus of Republicans. Well, that means that they’re going to focus on the Harris-Biden policy outcomes, right?

DIONNE: By the way, you just invented the way they’re going to talk about it. I note that you said Harris-Biden, not Biden-Harris. And I think that’s really interesting. And, yes, I think there is I mean, on the one hand, with Donald Trump in the race, it’s impossible to escape things getting very, very personal on both sides because, you know, on the Republican side there is a devotion to Trump, a personal devotion in his base that is extraordinary. And that’s part of a campaign. Among Democrats, there’s an enormous fear of what a second Trump presidency would, represent.

So, I think that, you’ll never get out of the personal. And I am absolutely certain there’ll be a lot of personal attacks on, Kamala Harris and what she may have said or done in the past. So, we’ll never get by that.

Having said that, I think the age issue was the single biggest issue that Biden had against him. It was the issue even Democrats said, even Democrats who were voting for him, said held them back or gave them doubts. And so, I do think there is an opening on issues. I think you will see, for example, Ukraine and support for Ukraine litigated partly because of J.D. Vance’s pretty strong skepticism of aid to Ukraine, which goes with Biden’s Democrats. The abortion issue may become even more prominent, partly because Harris has been the leading voice on reproductive rights issues for the last year in the Democratic Party. And because J.D. Vance has an even more sort of pronounced anti-abortion position than Donald Trump does.

And I think you’re going to litigate a lot of economic issues as well. And the Republicans want to talk about inflation and prices, and Democrats want to talk about the economic growth and wage growth over the last several years.

So, yes, I agree with my colleague that issues will become more important, and I certainly hope they do. But in this year, I think the personal is still the political in a very big way.

DEWS: Well, E.J., let’s finish this way. It’s it’s been just over 24 hours since this momentous event has transpired. And there’ll still be plenty of news to come. But do you think, so far at least, that this signals something about the health or the ill health of American democracy?

DIONNE: You know, I I think my short answer would be no. It doesn’t in this sense that the Democrats going into the year thought that Joe Biden would make it through the election as a prepared candidate and could make it through four years. There were people going in who said that was wrong. Largely, they lost the debate and Biden went forward.

When evidence came forward in that debate that there might be a negative answer to that question, a lot of people who had taken one position before, basically changed their minds, not because they changed their view on Joe Biden or his policy, but because there were new facts in front of them. And they decided, you know, what we thought could work didn’t work. And so, they turned around, changed their mind, and changed the nominee.

I think that that is healthier than not. That is a good sign. Now are there other signs of real trouble in our politics? Election denial? The fact that, you know, it’s still not clear that if Mr. Trump lost, it sounds like he still wouldn’t accept the outcome of that election. Are we deeply polarized? All those things are true.

And obviously the assassination attempt is deeply disconcerting. I don’t know what we can make of that in large terms. You can certainly make arguments about the availability of guns. You can make arguments about the tone of our politics. But what we know about the man who shot Trump, it does not there’s not any clear political motivation there. He was, it appears, a registered Republican. So, on the one hand, the shooting is horrifying. And violence in politics is horrifying. But I’m not sure what we are supposed to make. I think we can sort of elaborate a lot of stories about things like this, and they may not be about, you know, the things that we’re building the stories around, just that they’re bad.

DEWS: Well, E.J., it’s always illuminating to chat with you about, these issues. Thank you for sharing your time and expertise today, I appreciate it.

DIONNE: A real joy to be with you. Thank you so much.

DEWS: And I know we will hear from you again in the near future.

DIONNE: I look forward to it.

Commentary

PodcastAs Joe Biden exits the presidential race, what’s next for Kamala Harris

July 23, 2024