In this written debate, the authors address the title question with essay-length opening statements. The statements are followed by an interactive series of exchanges between authors on each other’s arguments. The goal of this product is not to reach any conclusion on the question, but to offer a rigorous examination of the choices and trade-offs that confront the United States in its competition with China.

Strategic competition between the United States and China is impacting how the two countries relate to each other across the world, including in Latin America. How are the United States and China approaching Latin America and where do their interests intersect? What is the character of their interactions in the Western Hemisphere—rivalry, cooperation, or something in between? And finally, should competition with China be used to motivate American policymakers to devote more attention and resources to Latin America?

These questions are examined by an expert group of scholars—R. Evan Ellis, Leland Lazarus, Ted Piccone, and Valerie Wirtschafter—in a written debate analyzing the nature of U.S. and China relations in Latin America. The exchange is the latest in the Brookings Foreign Policy project: “Global China: Assessing China’s Growing Role in the World,” convened by Ryan Hass, Patricia M. Kim, and Emilie Kimball. These experts will participate in a live debate moderated by Telemundo’s Arantxa Loizaga on October 4 in Miami. The opening written statements and reactions are below:

Valerie Wirtschafter

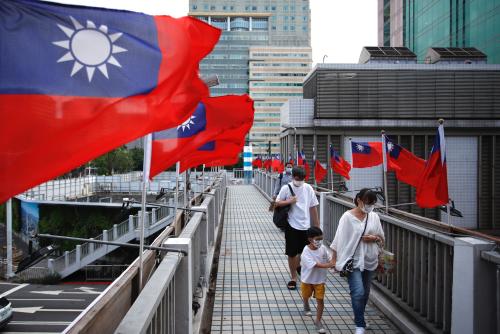

For the past two decades, China’s interests in Latin America have grown exponentially. Beijing’s objectives are threefold: economic, diplomatic, and geopolitical. With aspirations toward greater economic engagement, China’s trade with Latin America—including imports of raw materials and food supplies and exports of manufactured goods—has grown from around $18 billion in 2002 to over $450 billion in 2022. In tandem, China has sought to leverage this growing economic muscle to reshuffle regional alignments and isolate Taiwan. And in some countries, Beijing has engaged in more provocative attempts to counterbalance the United States’ presence in the Indo-Pacific. A recent report by scholars at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, for example, has found evidence of suspected Chinese spy facilities in Cuba, designed to glean signals intelligence about U.S. activities. More broadly, a Chinese security presence in parts of the region rattles Washington’s foreign policy apparatus.

The United States, by contrast, has for centuries maintained a vested interest in regional dynamics, at times for better and at times for worse. Due to geographic proximity, regional instability often ricochets to the United States through the southern border with Mexico. As a result, U.S. engagement often focuses more on immediate efforts to promote stability and curb migration flows, such as border security and assistance to reduce violence. These near-term challenges do not factor into China’s regional calculus, but they do limit the U.S. government’s ability to focus on longer-term objectives in Latin America, like expanding trade or environmental considerations. Recently, however, U.S. policymakers have also endeavored to counter China’s expansion, with a focus on deepening economic ties.

While China’s regional engagement—like spy facilities—is sometimes inflammatory, there may be areas where Beijing’s regional interests have benefited U.S. strategic objectives. There is some evidence, for example, that China’s investments in energy, infrastructure, and broader trade dynamics helped to create 1.8 million jobs in Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, and Chile between 1995 and 2016. However, the distribution of these jobs and their overall quality varies significantly by sector and country. Yet Beijing’s approach can also undermine some U.S. objectives as well. In the recent Venezuelan elections, for example, Chinese President Xi Jinping was one of the first leaders to congratulate Nicolas Maduro on an election victory that is widely considered to be fraudulent. This type of signal from Beijing offers important backing to a repressive, unpopular regime and hinders U.S. goals of ensuring regional stability. More broadly, China’s general disinterest in good governance can help to prop up corrupt, authoritarian regimes that otherwise have a damaging impact in countries throughout Latin America.

Presenting a more attractive alternative

In an era of geopolitical competition, many countries in the region have opted to reap the benefits of partnership with both the United States and China. Despite overt threats to decouple their respective economies from Beijing, leaders across Latin America—from Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro to El Salvador’s Nayib Bukele and Argentina’s Javier Milei—have continued to work closely with China, preferring a more expansive portfolio to fuel economic growth. In these contexts, the desire for diversification outweighs ideological disagreements, though it may also signal a growing dependency on Beijing too. It is also evident that voters value productive economic relations with China: Recent public opinion surveys from Mexico, Argentina, and Brazil underscore the belief that China’s engagement is viewed as a net positive.

Despite this sentiment, the region is growing increasingly weary of some of Beijing’s bad behaviors, including debt traps, cheap goods flooding the market and crowding out domestic manufacturers, poor sustainability practices, and a continued dependency on raw material exports to fuel Chinese demand. There is also some frustration with recent changes in the scale and scope of China’s regional investments, which have slowed significantly since their height during the 2010s. These developments have created an opening for Washington to present a mutually beneficial and more appealing alternative to China, particularly as it looks to “nearshoring” or “friendshoring” to reduce its own economic dependencies on Beijing.

The technology sphere, in particular, is a critical area that Beijing has continued to prioritize with more and smaller projects. At present, Beijing’s Digital Silk Road investments in Latin America focus on digital infrastructure, telecommunications, and technology. Major projects include building 5G networks, data centers, fiber-optic cables, and satellite systems, with companies like Huawei and ZTE playing leading roles. These partnerships, some of which were likely motivated by China’s leveraging of COVID-19-vaccines for other objectives, raise significant concerns about data privacy, cybersecurity, intellectual property theft, and surveillance.

Due to pricing constraints, the United States faces stiff resistance in countering some of Beijing’s technological aspirations. Yet there are some areas where the United States can make inroads. For example, aspects of the CHIPS and Science Act, which aims to build resilience into the semiconductor supply chain, offer huge openings for some countries in the region to build capacity beyond that of commodities exporters and move up the value chain for an increasingly critical industry. Evaluating the viability and following through on some of these opportunities could offer a path forward for the United States and regional countries to forge productive, sustainable economic engagement that elevates regional growth and prosperity. What is certain is that without an alternative to Chinese investment, any Cold War-style, “us or them” approach that appeals to shared values or security concerns alone is likely to remain unpersuasive.

Moving forward, it would be welcome if competition with China increases Washington’s attention to the region. However, it will also be critical to go beyond geopolitical competition to address shared challenges across the Western Hemisphere. Given Latin America’s proximity to the United States and its clear importance for U.S. stability, Washington must pay greater attention to the region. In the past 12 years, Xi has traveled to 13 Latin American and Caribbean countries, while U.S. leaders have made nine such trips during the same period (and just three in the past eight years).

The cultural and personal linkages between the United States and the region are also a huge asset. Leveraging these shared ties and supporting practices that promote good governance throughout the region—particularly in countries where support for democracy remains high—will go a long way toward countering China’s transactional approach and strengthening engagement between the United States and Latin America.

Leland Lazarus

For decades, most China-Latin America watchers focused on trade and economics. And for good reason. Today, the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) trade with Latin America and the Caribbean totaled $450 billion, up from just $18 billion two decades ago. The PRC is now South America’s main trading partner, and trade has expanded far beyond just raw materials and commodities to include traditional infrastructure (roads, bridges, ports) and “new infrastructure”: electric vehicles, telecommunication, and renewable energy. 22 countries in the region have joined the PRC’s Belt and Road Initiative, and Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s recent remarks suggest his country may soon follow.

Yet trends and facts show that certain PRC activities in the Western Hemisphere infringe on the sovereignty that so many Latin America and Caribbean countries cherish, and potentially threaten U.S. national security.

PRC infrastructure projects could be “dual-use”—blending commercial and security purposes. PRC state-owned enterprises (SOEs) have built, currently own significant stakes in, or are looking to invest in ports across the region, especially near key waterways like the Panama Canal, the Strait of Magellan, and the Caribbean Basin. Such projects could give PRC SOEs significant leverage over maritime traffic close to the United States. The PRC’s 2017 National Intelligence Law requires all companies—including port operators—to cooperate with PRC security and intelligence services. During a potential conflict with the United States in the Taiwan Strait or the South China Sea, the PRC government could order these port operators to try to restrict or delay U.S. commercial or naval access. In Equatorial Guinea, the United Arab Emirates, and Cambodia, the PRC reportedly has ambitions to use commercial ports for military purposes; it may do the same in Latin America in the future.

Surveillance and espionage are another concern. PRC spy bases in Cuba could enable the PRC to intercept communications from U.S. military and space facilities in the southeastern United States. In addition, PRC companies Huawei, ZTE, Dahua, and Hikvision have set up “Safe City” technology in various Latin American cities, comprising advanced surveillance systems and enhancing local law enforcement capabilities but also raising concerns about potential misuse for espionage. Nuctech and ZPMC provide cargo scanners and port cranes in several ports, raising alarms about data security and critical infrastructure vulnerability. Earlier this year, the U.S. government warned U.S. port operators about using Nuctech and ZPMC equipment because they could collect sensitive commercial data and biometric information, or install malware in port systems.

PRC entities also have their eyes on space. PRC organizations—some with direct ties to the People’s Liberation Army (PLA)—operate 11 satellite tracking stations across South America. These facilities, ostensibly used for space research and satellite tracking, could also track or interfere with U.S. and other partner satellites. For instance, the infamous Espacio Lejano site in Neuquén, Argentina, was built by a subsidiary of the PLA’s Strategic Support Forces. Some researchers have even argued that these sites could help the PLA guide hypersonic missiles, potentially boosting the PRC’s capability to strike the U.S. homeland.

Chinese illegal networks are also expanding operations throughout the Western Hemisphere. PRC-based chemical companies ship fentanyl precursors to Sinaloa cartel members, which then make them into potent pills that have killed more than 100,000 Americans a year. Chinese organized criminals based in the United States and Mexico have become the main money launderers for the Sinaloa cartel, and have set up thousands of illegal marijuana farms from Maine to California. Elsewhere in Latin America, other Chinese illegal groups traffic wildlife, launder money, and smuggle humans. Some of the tens of thousands of illegal Chinese migrants entering the U.S. southwestern border are being exploited by these networks, becoming victims of forced labor or prostitution. These groups also engage in selling drugs, human smuggling, sex trafficking, illegal mining, fishing and logging, gambling, and other crimes. While there are no clear links between the PRC government and these illegal groups, reports by the House Committee on the Chinese Communist Party, former U.S. officials, and journalists suggest that some PRC officials either turn a blind eye to or directly benefit from their illicit activities.

Beyond these national security concerns, the PRC has also been boosting its security cooperation in Latin America and the Caribbean. In recent years, the PRC has hosted dozens of country law enforcement officials for law enforcement training, donated vehicles and equipment to local police, and established overseas police stations across the region. Through these activities, the PRC may be exporting its repressive surveillance state practices and pursuing dissidents abroad.

Understandably, U.S. national security officials and members of Congress have raised alarms about these multifaceted threats. But pressuring our regional partners to stop all business with the PRC isn’t feasible or realistic. Most Latin American leaders want to trade with both the PRC and the United States. They often criticize the United States for not providing enough alternatives to PRC lending and dismiss U.S. warnings as simply the former imperialist power trying to revive the Monroe Doctrine, dictating how the region should conduct its foreign policy.

A wiser strategy is to appeal to our regional partners’ sense of sovereignty. The United States should encourage countries to develop investment screening mechanisms similar to the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States to ensure PRC-built infrastructure projects don’t infringe on their sovereignty and security. U.S. intelligence agencies should refrain from over-classifying the intelligence that country leaders need to understand the risks of relying on PRC SOEs for key infrastructure. More often than not, the United States isn’t the best messenger; instead, the United States should facilitate exchanges between Latin America, Africa, and Southeast Asia so that they learn from other Global South countries on how best to maximize their relations with the PRC. U.S. agencies and like-minded nongovernmental organizations should expand training to local investigative journalists and civil society organizations to expose the PRC’s malign activities in the region and to keep local policymakers accountable.

Most importantly, whoever wins the U.S. November election must resist the temptation of reinventing the wheel by creating a whole new regional strategy. The new president must build on the Americas Partnership for Economic Prosperity, which focuses on resilient supply chains, digital connectivity, and a semiconductor ecosystem.

Finally, instead of looking at Latin America mostly through the lens of migration and drugs, U.S. policymakers should view the hemisphere as a region of promise—one that can lead in new areas such as semiconductor assembly, packaging and testing, financial services technologies, and critical mineral production to fuel the global green transition and artificial intelligence revolution in the 21st century.

R. Evan Ellis

U.S. prosperity and security are tied to Latin America by bonds of geography, commerce, and family. Whether or not the United States gives the region the strategic thought or resources that its importance merits, its conditions and difficulties profoundly impact the United States as a matter of domestic and foreign policy, including through drugs, migration, and supply chains.

PRC engagement with Latin America is not all negative. PRC-based companies, when properly selected and supervised through strong Latin American institutions in transparent transactions, can contribute to the region’s commercial vitality and infrastructure. Too often, however, without the application of adequate transparency and institutional capability on the Latin American side, predatory PRC contracting practices, improper collusion among PRC entities, and the offering of personal benefits, lead to deals in which the Chinese, rather than local partners, capture a disproportionate share of the value added. They also frequently lead to poor project performance, environmental damage, social conflict, and information security risks. Because China’s 2017 national security law obliges PRC-based companies to give the state access to data if it so demands it, the increasing dominance of those companies in digital sectors across the region, including telecommunications, cloud computing, security systems, scanners, and ride-sharing apps, all raise concern over exploitable PRC access information on decisionmakers, governments, and rival companies in the region. In addition, PRC commodity purchases, loans, surveillance systems, and other forms of support to authoritarian regimes such as Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Cuba, as well as acceptance of problematic practices by others (as long as PRC-based companies are treated well) fundamentally undercuts democracy and good governance in the region.

In the undesirable event of a major war between the United States and the PRC, Latin America and its infrastructure, including its ports, digital architectures, and space facilities, will be logical targets for the PRC and aligned forces. The PRC will seek to exploit these assets to disrupt U.S. deployment, sustainment, and other Indo-Pacific-focused operations that pass through or can be reached from locations in Latin America and the Caribbean, and for Chinese warfighting initiatives to put the U.S. homeland, and those supporting the U.S. position, at risk. The United States and Latin America’s shared geography makes sustaining healthy democratic institutions in the region a vital U.S. interest. The United States is also well served by cultivating relationships with friendly governments that are willing to work with the United States in managing such challenges, pursuing joint opportunities, and preventing extra-hemispheric U.S. rivals, including the PRC, Russia, and Iran, from establishing regional positions they could exploit against the United States in time of conflict.

U.S. and Chinese interests in Latin America are dramatically different. In contrast to the aforementioned inherent U.S. stake in the region’s political and economic conditions, geographically distant PRC-based companies focus on the region’s resources and markets, which does not naturally carry the same stake in the region’s conditions beyond those facilitating access by, and good treatment of, PRC-based companies. Nor are the PRC or its companies inherently interested in their engagement’s environmental, developmental, political, or other consequences beyond the damage caused to their reputations and the credibility of the “south-south” collaboration message that facilitates their access. The PRC also diverges from the United States in two other ways: The PRC remains interested in “flipping” the diplomatic posture of and expanding its influence in countries formerly recognizing Taiwan, and the PRC retains an indirect interest in the survival of illiberal regimes such as Cuba, Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Bolivia, whose survival distracts the United States and undercuts its influence. The PRC’s support for these regimes also undermines democracy and facilitates regional instability through refugee and narcotics flows and these states’ decisions to host terrorist and criminal groups with transnational reach. The PRC does engage with democratic regimes, seeks to avoid association with authoritarian states’ bad behaviors, and positions itself to sustain economic relations if they change, yet it is notably neutral on facilitating good governance and democracy in the region.

In areas such as security cooperation and infrastructure, the PRC’s previously noted potential to exploit such positions for commercial or political espionage, or in time of war, makes the strategic risks of U.S.-PRC cooperation unacceptable.

On a more positive note, in some areas, such as trade and investment, Latin America’s engagement with the PRC has the potential to support the region’s economic health in ways that are consistent with U.S. interests. Critically, however, the region’s hopes for such positive outcomes require strong institutions, transparency, and a level playing field to ensure that often predatory Chinese business practices benefit the country instead of producing outcomes that disproportionately benefit the PRC-based companies and the local officials they persuaded to authorize the deal. As Chinese influence in the country grows, vigilance, transparency, and strong institutions are also vital to ensure that the PRC’s influence networks with local partners, and the hopes of future benefits, do not distort countries’ democratic discourse or empower non-democratic local elites to consolidate power in non-democratic ways. When political change does allow new governments to expose corruption, poor performance, abusive contracts, and other problems in their predecessors’ non-transparent dealings with the Chinese, as occurred in Ecuador, Argentina, and elsewhere, it is important to leverage such information as a cautionary tale for others.

The region generally seeks economic opportunity without strings attached, from both the United States and China. Its elites are generally aware of the risks that PRC-backed projects could turn out poorly, with excess environmental damage, social unrest, or limited benefit to the country or the local partner. Those engaging the Chinese nonetheless calculate that they can manage such risks, in hopes of securing the personal, commercial, and/or national benefits. Their rejection of U.S. words of caution, in the name of not “taking sides” in “great power competition,” may be sincere, but it also deflects a fuller consideration of such risks within their political systems.

In consideration of the aforementioned dynamics, the United States should not attempt to block the region’s sovereign right to engage in legitimate business with the PRC. Rather, the United States should lobby for transparency in such dealings, including in public tenders and contract terms, while collaborating to strengthen the region’s institutions to maximize the benefits that each country secures from all of its partners, to pursue its long-term development and security, and to protect its environment and the stewardship of its resources.

The region’s strategic importance makes it imperative for the United States to dedicate more national leadership thought and resources to it. This should include not only government programs but also more effectively leveraging the private sector. The U.S. government should also rethink policy imperatives that require U.S. assistance to concentrate on sectors such as renewable energy, women, and disadvantaged populations, and that limit engagement with “high-income” countries. These imperatives’ current excess inhibits the United States’ ability to compete with China by excessively constraining where the private sector puts its money, thus limiting the amount of money provided through such programs.

Ted Piccone

As a region one step removed from the front lines of the growing strategic competition between the United States and China, Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) may appear less important to the overarching geopolitical contest between these two powers. Yet China’s dramatic expansion of activity in the LAC region across multiple domains (financial, political, commercial, and security) and sectors (from presidential palaces to mayors to local businesses and media) has upped the ante in Washington as leaders from both political parties look to counter Beijing across the board. The region’s governments will likely remain below the fray by extracting the investments, support, and respect they seek from both countries without getting entangled in a direct superpower conflict.

The United States should be worried about China’s growing influence in a region so geographically, politically, and culturally close to its shores. Over the last decade, China has been sowing the seeds of a multifaceted strategy to exert real pressure on the region’s governments, which could be used to help counter direct threats to its regime—e.g., a conflict over Taiwan or a revived pro-democracy movement. Its posture as a so-called friend to the developing Global South will enable it to continue to secure some win-win outcomes, such as in building infrastructure and technology or solidifying ties with specific countries such as Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Bolivia.

A confrontational U.S. response, however, risks falling into a well-worn trap of seeing the region only through a global security lens, as happened during the Cold War, the war against drugs, and the war against terrorism.

The United States would be better off pursuing strong bilateral and regional relations founded on mutual interests and the values of building stable and healthy market democracies. Such partners would be capable of cooperating with it on priorities such as reducing illegal migration, combating cross-border crime and trafficking, lowering poverty and inequality, controlling climate change, and shoring up democratic institutions. In those countries where these interests align, a positive and well-resourced U.S. strategy to empower the region’s reformers, rather than demanding fealty to challenge Beijing at every turn, would have a better chance of success over the short and long term.

If or when China pivots toward a more directly hostile stance against U.S. interests in the region, however, Washington should be ready to push back in ways that minimize traditional anti-American resistance.

China’s long game

China’s core interests in the region are straightforward: it primarily seeks to secure the energy, metals, and food inputs it needs to fuel its economy and to expand export markets for both heavy and retail manufactured goods and, increasingly, technology products. Secondarily, it sees the region as a zone of competition with its diplomatic rival, Taiwan (the Republic of China), which retains recognition and support from a (declining) number of sympathetic LAC governments. Third, it looks to compete with the United States in its own neighborhood in part to reciprocate, at least symbolically, Washington’s long-standing and robust security presence in China’s geographic orbit. Finally, Beijing wants to support ideological and other fellow travelers such as the Maduro regime in Venezuela and the entrenched post-Castro leadership in communist Cuba, though judging from the ongoing crises in these two countries, this policy has its limits.

The overarching goal driving these interests is the Chinese Communist Party’s obsession with preserving power, which requires high rates of economic growth to continue its quest to build a “Chinese dream” of middle-class security and to underwrite its territorial claims in its perimeter. As a mixed system of state-led capitalism and severe Leninist autocracy, with ambitions to restructure the international order to advance its own grip on power, China under Xi Jinping is inherently a negative partner for LAC countries committed to political pluralism and free enterprise. Its lack of transparency, chronic corruption, human rights abuses, and weak labor and environmental record, coupled with its heavy-handed “wolf warrior” diplomacy, are giving both public and private leaders in the region pause as they negotiate their way toward greater interdependence.

Given their disparate and diminished individual agency to maximize their own interests, like-minded countries in the region that are worried about China’s role should try to downplay their differences and find some common ground among themselves to ensure China does not overtake them, while reinforcing their own domestic governing institutions against Chinese and others’ predations.

The U.S. conundrum

Washington is perennially faced with a dilemma of how to pursue its own interests in its southern neighborhood. Saddled with a long and ugly history of interventionism, the broad consensus is to turn the page toward more cooperative partnerships that prioritize building stronger democratic states across the region. Unfortunately, other than Chile, Costa Rica, Uruguay, and several small Caribbean states, LAC governments remain far from that ideal. Urgent security problems brought on by violent criminal groups and transnational gangs, including deadly cross-border drug and gun flows, entrenched corruption, weak rule of law, and unmanageable migration, are having direct, adverse effects on U.S. communities and torquing U.S. domestic politics toward more hardline policies.

Getting to the root causes of these problems requires a comprehensive and much higher-resourced U.S. strategy. This could include more support for financial and social services, greater cooperation between law enforcement agencies, increased incentives for nearshoring opportunities to draw manufacturing away from China, and continued sanctions against autocratic and corrupt leaders like Venezuela’s Nicolas Maduro and Nicaragua’s Daniel Ortega. Ironically, the more democratic the region becomes, with its attendant political swings and uncertainties, the more difficult it is for the United States to devise such a cohesive and effective roadmap to greater stability. It too must play the long game to succeed, but it faces its own internal political tribulations that often make the region a scapegoat for problems that require shared solutions—e.g., illegal migration, small arms trafficking, and illicit drug trafficking.

Regardless of China’s behavior, the next administration would be wise to work closely with Congress to significantly ramp up its development, good governance, and law enforcement assistance to targeted countries and problems in ways that would boost livelihoods and security on both sides of the border. If playing the China card as an additional argument for boosting investment in the region helps, so be it.

Responses

Leland Lazarus

One key thread in all four essays is that the United States shouldn’t revert back to a cold-war-style approach to PRC-Latin America relations. Wirtschafter and Piccone rightly point out that such a confrontational approach will backfire. Evan Ellis avers that the United States shouldn’t attempt to “block” Latin American countries from engaging in legitimate business with the PRC, and instead offer viable alternatives.

The good news is U.S. policymakers are listening and acting. In early September, the State Department hosted the Americas Partnership Semiconductor Symposium, bringing together Mexico, Costa Rica, Panama, and the Dominican Republic to expand semiconductor assembly, testing, and packaging. The U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) has invested more than $11 billion in projects across the Western Hemisphere, such as loans to Honduran small businesses, funding for Brazil to cleanly extract critical minerals, and risk insurance to help Ecuador conserve the Galapagos Islands. The DFC has also partnered with the Inter-American Development Bank and the U.S. Agency for International Development to jointly finance projects and is actively encouraging more U.S. private sector engagement.

The United States doesn’t have to go it alone. It must also work shoulder-to-shoulder with its allies and partners to pool resources and jointly fund big ticket infrastructure. In 2023, the European Union pledged €45 billion through its Global Gateway initiative for green energy transition, digital connectivity, and health. Taiwan is already working with the DFC on small business centers and climate resilience in its seven diplomatic allies in the region. Japan—with a large diaspora in Brazil and auto companies with investments from Mexico down to Argentina—can also play more of a key role. South Korea aspires to be a global pivot state, and a Korean company is looking to deepen its lithium investments in Argentina and Chile. India’s foreign minister said his country should double trade with the region by 2027, and the African Export-Import Bank is looking for investment opportunities too. The United States and its allies are already doing this kind of blended financing in the Indo-Pacific; they should do the same in this hemisphere too.

Finally, Wirtschafter highlights the deep cultural and personal linkages between the United States and the Americas. But cultural and academic exchange programs have been chronically underfunded. As a U.S. diplomat in the Caribbean, I saw how our embassy proudly announced five Fulbright scholars going to the United States But days later, the PRC embassy announced that it sent dozens of students to China.

The United States must boost funding for the Fulbright Program, International Visitor Leadership Program, Young Leaders of the Americas Initiative, and others. Doing so will ensure that more future leaders will enjoy genuine experiences in the United States, which will hopefully encourage them to advocate for U.S.-aligned policies years down the road. Otherwise, young leaders receiving the red-carpet treatment from Beijing today may become stalwart PRC allies tomorrow.

Ted Piccone

My colleagues and I agree on the fundamentals of the growing competition between the United States and China and its implications (bad and good) for the Latin America and Caribbean region. We also concur that a hard-line campaign to pressure Latin America and Caribbean governments to disengage from such a vital partner as China would likely backfire. There is also strong consensus, well-articulated by Lazarus, that China is positioning itself to exploit its expanding presence in the region to suit its own security and economic interests at the expense of Latin America, Caribbean, and U.S. interests.

The tougher question is whether to view the region principally as a theater for the overarching U.S.-China competition or as a critical zone of vital U.S. interests deserving of much greater attention and resources from Washington regardless of the China threat. History tells us that when U.S. policymakers and politics look at the region mainly from a global threat perspective, more friction than cooperation erupts. When we see the hemisphere as a collection of troubled but mostly friendly democratizing societies, we get better results, ranging from President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Good Neighbor Policy to President Bill Clinton’s Summit of the Americas. The current debate between a revival of the Monroe Doctrine advanced by some conservatives and a more nuanced “root causes” strategy taken by the Biden-Harris administration reveals the ongoing tension between these two approaches.

Unfortunately, the relatively benign environment of the 1990s has eroded due to an alarming conjunction of malign forces in the region—rising organized crime and very high levels of violence; entrenched autocracies in Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Cuba; weak governing institutions and rule of law; and anemic economic performance and high inequality. China, unfortunately, tends to be aligned on the wrong side of most of these issues. Even in the area of trade and investment, China’s behavior leans toward predatory practices, lack of transparency, and a short leash from the Chinese Communist Party’s levers of power and influence. China’s ramped-up information operations in the region further underscore the concerns all four of us have for a more troubling constellation of threats.

Given official Washington’s traditional neglect of the region, a more realistic approach, and one that would garner some bipartisan support, would be to use the China card at home as an argument for a long overdue intensification of U.S. investment and outreach across the board. The key elements of a robust strategy toward the region would include expanded nearshoring opportunities, judicial and law enforcement cooperation, science and technology upgrades, renewable energy and climate change mitigation and adaptation, and education and cultural exchanges. Abroad, the message would lead with a frame of good neighbors working together to solve common challenges.

R. Evan Ellis

In our essays, my colleagues generally agree that PRC engagement impacts not only the region’s economies but also its political dynamics and discourse, presenting important security issues that affect U.S. interests. Yet while the region widely perceives that the United States seeks to force a choice between it and China as a partner, that has actually never been the actual policy, neither under President Donald Trump nor President Joe Biden. That perception, however, is problematic for the U.S. relationship with the region, as is the common assumption that the principal way for the United States to “compete” with China is by providing more resources to solve the region’s problems. That course oversimplifies both the limits of the U.S. market-based, democratic political system and its institutions, as well as the risks posed by the PRC, to which the United States must effectively respond.

Lazarus’ admonition that “It’s more than the economy, stupid,” highlights the cognitive dissonance in a region that facilitates China’s advance. Those hoping to secure the benefits of engaging with the PRC discount not only the business risks but also the strategic implications that come with dependence on Chinese money, Chinese contracts, information architectures, the operation of dual-use port and space facilities, “people-to-people” influence networks, and security relationships.

Piccone’s admonition not to look at PRC activities in the region through a “security lens” illustrates the dilemma of U.S. engagement. In the event of a conflict, the PRC’s relationships with and commercial presence in the region, particularly in sectors such as ports and space, give it significant options that would be logical to exploit against the United States in the context of a war. While the United States must respect its partners’ sovereign choices and search for economic benefit in peacetime, it must also prepare for and work to mitigate those risks today, since doing so in wartime will be too late.

Piccone’s good argument about the need for more U.S. resources to help address the “root causes” of the region’s problems similarly illustrates the need for U.S. policies that address the region’s needs, without inadvertently undermining the U.S. strategic position. As suggested by Chile and Uruguay, prosperous, secure partners with healthy democratic institutions are less vulnerable to predatory PRC practices and less likely to permit PRC engagements that introduce significant security risks. Yet uncritical U.S. support for needed regional development projects in sectors such as renewable electric power and digital infrastructure, where PRC-based firms are dominant, may accelerate PRC influence, digital espionage, and wartime risks. Nearshoring, as Wirtschafter mentioned, is a similar example. “Decoupling” has fueled a shift in production for the U.S. market to Mexico rather than China, thereby driving a major influx of PRC-based companies into Mexico, with an associated jump in risks to supply chains touching the United States and wartime vulnerabilities.

Valerie Wirtschafter

I think it is very telling that for the most part, we all landed on two similar points in our initial responses, albeit with significant nuances and minor divergences throughout. The two trends that I see running through most if not all of the initial reactions are: (1) the belief that to counter Chinese expansion in the region, the U.S. government needs to devote additional attention and resources to Latin America than it does right now, particularly given the salience of the region to domestic political dynamics; and (2) the United States should not force leaders in the region to choose between engagement with Washington or engagement with Beijing, but rather present a better proposition to the region. These have been and continue to be vital pillars of a productive relationship with regional partners and seem to be important guiding principles in shaping how the United States should approach China’s growing role in the Western Hemisphere.

What I do hope for, and I think Piccone’s response gets to this point effectively, is that we can extend beyond the question of countering China’s role in shaping the United States’ engagements throughout the region. Latin American and Caribbean countries are too important to U.S. foreign and domestic policy to be driven entirely by this geopolitical contest. Regional challenges like migration, drug and arms trafficking, climate change, transnational crime, economic growth, and many others are critical to U.S. stability, with or without China in the fray. If China is the entry point for policymakers, so be it, but the need for collaboration is too deep to stop there.

Commentary

How are the United States and China intersecting in Latin America?

September 25, 2024