For the Biden administration, Syria’s ongoing conflict is a minor irritant that occasionally forces itself onto the agenda but for the most part can be ignored. Containing the conflict’s spill-over effects—whether in the form of refugees, narcotics smuggling, friction with Turkey over U.S. support for Kurdish actors and the presence of U.S. forces, or the humanitarian effects of economic collapse—defines the limits of the administration’s interest in Syria. The Islamic State’s resurgence is largely outsourced to Kurdish partners. The diplomatic commitment that would be needed for progress toward the comprehensive political solution set out in U.N. Security Council Resolution 2254—now almost a decade old—is no longer seen as a priority. Even the administration’s opposition to the normalization of the Assad regime has become pro forma.

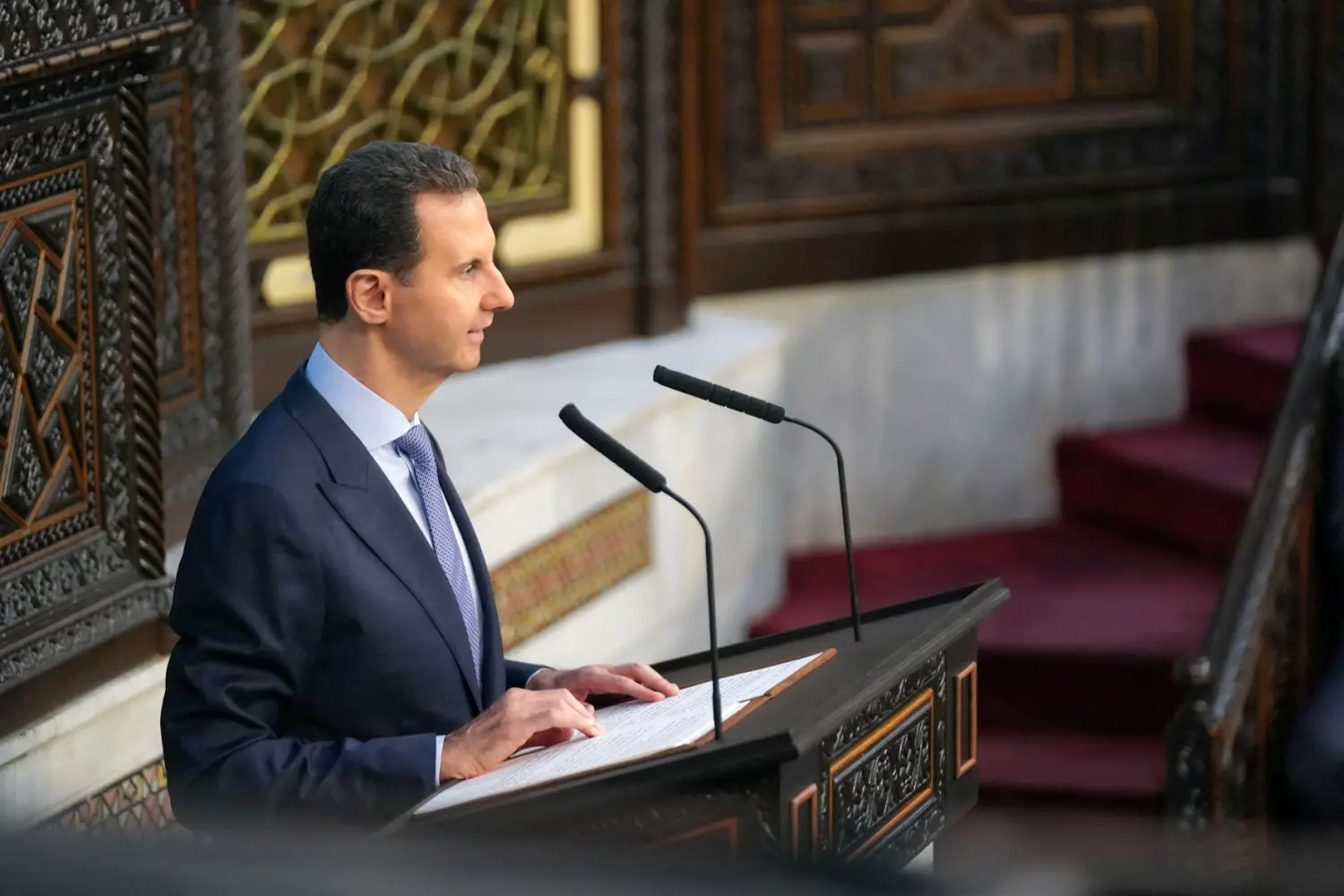

As Syria slips from official and public view, however, less and less attention is directed toward the Assad regime, how it keeps itself afloat, and how recent shifts in the tactics it uses to insulate itself from both economic sanctions and an increasingly restive society are likely to fuel the effects that the United States and its allies view as most threatening. These include further increases in refugee flows, a worsening humanitarian crisis, and renewed waves of radicalization. Out of public view, and even as Syria continues to be plagued by many different vectors of crisis, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and his innermost circles are reorganizing how they intervene in and manage the country’s economy.

In recent years, Assad has deepened his grip over crucial economic sectors, using networks of frontmen and women to position himself as a powerful economic actor and give himself and his regime the space to resist the use of economic pressure as an instrument of coercive diplomacy. This shift, intentionally obscured by the regime and overlooked by its adversaries, is evident from a close analysis of the economic networks that Assad has constructed around himself. Unpacking these networks and their implications is essential for the United States and its allies to ensure the effectiveness of policies intended to isolate and hold accountable a regime that is directly complicit in some of the worst war crimes and crimes against humanity of the 21st century.

Economic networks have long been central to the regime’s survival strategy. Since the start of the conflict, however, the Assad regime has placed increasing weight on those economic networks. Business cronies closely tied to Assad have played crucial roles in sanctions avoidance, securing essential goods, concealing assets, and enabling the elite to maintain its privileged lifestyle in the face of economic collapse. Over time, Assad and his inner circle have become adept in managing crony networks to keep the regime afloat, adjusting who’s in and who’s out to ensure that the money continues to flow.

As Assad discovered in 2019, however, when his cousin and once-trusted bag man Rami Makhlouf resisted turning over assets accumulated in part on Bashar’s behalf, cronies have minds of their own. To recover what was reported to be billions in assets, Assad oversaw the systematic dismantling of Makhlouf’s economic holdings. In the aftermath of his confrontation with Makhlouf, Assad has moved to secure direct control over the former’s economic empire, dramatically restructuring the informal networked ecosystem he depends on. These changes, visible for the first time through our analysis of firm-level micro-data and open-source research, offer important insights into the inner workings of the upper reaches of the Assad regime and how conflict has transformed Syria’s political economy. This restructuring helps to explain Assad’s economic resilience in the midst of the economic crisis, why he has rejected step-for-step diplomacy despite its promised economic payoffs, and how the regime has been able to navigate a vast web of sanctions that directly target regime networks—networks that countries imposing sanctions and struggling to reach a political settlement fail to understand.

Understanding how Assad is changing Syria’s political economy is not a small matter. The benefits that accrue to Assad as a result of his new economic roles influence his strategic calculus. Feeling more confident about his own economic prospects affects how the regime engages with regional and international actors. It has a bearing on what the regime might be prepared to offer, or withhold, at the negotiating table. It also matters in determining who wins and who loses in Syria’s wartime economy and any potential reconstruction, issues of enormous relevance for the future of the Syrian business community. For the United States and other countries that continue to reject the path of normalization, exposing these networks sheds light on the architecture of corruption in Assad’s Syria and the policies needed to counteract it.

Background: Intransigence and resilience amid crisis

More than 13 years after the onset of Syria’s conflict, the country’s economy remains mired in crisis. Since 2011, the lira has lost more than 99% of its prewar value. In an assessment published in May 2024, the World Bank found that household welfare has collapsed, along with trade, agriculture, and manufacturing. More than 90% of Syrians now live in poverty. In its desperation to reduce spending, the Assad regime has added to ordinary Syrians’ hardships by cutting subsidies and tightening its grip over the economy, provoking sporadic protests across the country, even in areas that have remained quiet for a long time, including Damascus. In 2020, economic grievances ignited protests in southern Syria that have since morphed into a localized insurgency. Just as ominous from the regime’s perspective is a parallel decline in humanitarian assistance. At the same time, the support from key patrons continues to wane, with Iran’s oil exports to Syria at their lowest levels since 2020.

How is the Assad regime coping with economic collapse? In the face of withering conditions, it has turned its back on arguably its best prospect for economic relief and a start to economic recovery. Just over a year ago, Syria was reinstated as a full member of the Arab League, a significant step in its return to the Arab fold. In extending recognition and legitimacy to the regime, Arab states hoped to jump-start a “step-for-step” process of normalization that would include the provision of sorely needed financial support in exchange for the regime’s cooperation on issues of vital importance to its neighbors, notably stemming a flood of narcotics flowing out of Syria into the region, and concrete steps to facilitate the safe return of refugees. To advance negotiations about the steps Syria must take and what it would get in exchange, the Arab League established a Liaison Committee, including representatives from Jordan, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and Egypt.

As it turned out, the hopes of Syria’s neighbors were ill-founded. On May 7, 2024, exactly one year after Syria’s readmission to the Arab League, the Arab Liaison Committee suspended its meetings. Until now, despite the prospect of financial support, the Assad regime has refused to offer meaningful steps to address regional concerns. Its recalcitrance underscored the failure of the step-for-step approach and the limits of normalization to incentivize change in the regime’s conduct. It also made clear that the suffering of Syrians is a price the regime is willing to pay to avoid compromise.

The question raised by the regime’s rejectionist stance is why. What explains its refusal to accept even token shifts in policy if doing so would bring badly needed economic relief? Many factors play a role. Assad and his inner circle have long viewed any form of concession as signaling weakness. His regime, like his father’s, has mastered the art of foot-dragging to outlast adversaries at the bargaining table. Moreover, the willingness of Arab regimes to keep normalization alive despite its failure to deliver has persuaded Assad that he can get something for nothing. All these factors matter, but there’s more happening beneath the surface: Assad is reorganizing economic networks to bring key sectors of the economy under his direct control.

Assad’s economic networks

Through close analysis of micro-data on company formation in Syria and publicly available government statements and news articles compiled by the Observatory of Political and Economic Networks (OPEN),1 it is now clear that Assad is engineering changes in the informal economic networks that have long underpinned the country’s political economy. Since 2020, Assad has moved to reduce the unpredictability associated with his reliance on the cronies who own firms that were among the regime’s leading sources of revenue—alongside narcotics smuggling and aid diversion. To all outward appearances, what Assad seems to have learned from the Makhlouf episode of 2019-2021 was that only by centralizing and simplifying network structures and taking a leading, albeit hidden, role in the firms that underpin networks can he guarantee a reliable stream of revenues that flow directly into the president’s personal coffers. The peak cronies that rose to positions of influence since 2011, businessmen like Samer Foz, Muhammad Hamsho, and Hussam Qatarji, continue to occupy central roles in crony networks. Yet they increasingly operate alongside the networks controlled by Assad himself and his handpicked fronts and cut-outs. Assad seems convinced that instead of relying on cronies, he is better served by carving out a direct role as Syria’s dominant economic, as well as political, actor.

Assad’s newly minted networks and their reliance on business fronts are distinctly different from the economic networks that developed around traditional cronies. While cronies have physical offices, work addresses, and public profiles that they care about and promote, fronts have none. Despite the business empires that documents suggest the fronts control, they are ghosts to the public at large. In fact, among the five fronts identified here, only one, Yasar Ibrahim, has a publicly available photo, in contrast to cronies who often go to great lengths to cultivate public brands. Furthermore, while cronies provide political and economic support in exchange for the preferential treatment they receive from state institutions, enriching themselves in the process, business fronts have nothing to offer in exchange for the privileged positions they occupy. Their mere existence as “businessmen” rests on one factor alone: Assad’s approval. In fact, one of the five business fronts mentioned here is a state employee. Yasar Ibrahim is an adviser to Assad and head of the economic and financial office of the presidency. Further, the cronies’ scope of economic activities is not limited to those they undertake on the regime’s behalf, whereas fronts occupy more limited positions that more directly serve Assad’s economic interests.

The emergence and rapid growth of these new economic networks are only visible through close analysis of firm-level and investor-level data that sheds light on the formation of businesses by individuals with little to no prior business presence but with close ties to Assad. These ties are displayed in the following interactive figure. The subset of OPEN’s database presented in the illustrative tool is sourced from the Syrian Gazette, official government announcements, the Damascus Stock Exchange, and open-source news articles. Further information about OPEN’s data model and sources can be found here.

The network shows 11 individuals consisting of the Assads; the presidential advisor for media affairs, Luna al-Shibl, who died recently; the al-Bazzal brothers; notable Hezbollah financiers; regime crony Amer Foz; and five business fronts, namely Yasar Ibrahim, Ali Najib Ibrahim, Ahmed Khalil Khalil, Ramya Hamdan Deeb, and Razan Nizar Hmerah. The network also covers 19 entities, nine of which are front companies, which in turn partially own or operate three public sector entities, three established businesses with strong ties to regime cronies, and other transitory entities that bridge the gap between various network components. For the sake of simplicity, the interactive tool presents only a few front businesses. OPEN’s database identified 42 more businesses.

As the time slider in the network map shows, front companies were incorporated as early as 2015 with the establishment of Al-Ahed Trading and Investment. However, the front companies did not become active until 2018, with Al-Ahed taking up a share in the Syrian Modern Cables Company, which was initially owned by the Grewaty family who later had their assets frozen when their loyalty to Assad came into question. After the company’s assets were frozen, the company reappeared in government documents with a decision to elect a new board of directors. It was also revealed that the new owners of the company were the Al-Ahed Trading and Investment Company (50% of which is owned by Yasar Ibrahim), District Four Limited, and Amer Foz. On March 17, 2021, a government decision was issued to amend the project’s objective, confirming that the project’s ownership had transferred to the new company owners.

However, the number of fronts and the reach of their activities only became evident with the regime’s severe economic squeeze between 2019-2020, the result of the Lebanese banking crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the passage of the Caesar Syria Civilian Protection Act in the United States.

Networks and the economics of political survival

These business networks are an important addition to the arsenal of tools Assad has at his disposal. First, front networks that are subordinate to Assad liberate him from the uncertainties inherent in partnerships with crony business elites—no matter how trusted they appear—whose interests may not align with his own. Following Assad’s experience with Makhlouf, who resisted turning over assets to him, firms headed by his fronts offer the assurance of more predictable access to firm profits.

Second, Assad is positioning himself as a major direct beneficiary of the cannibalization of the state, the privatization of public assets, and the capture of state expenditures, giving new meaning to the phrase “Suriyya al-Assad” (“the Syria of Assad”) and further eroding distinctions between the public budget and the Assad family’s personal finances. While the regime’s crony business partners have typically benefitted from privileged access to public resources—and immunity from the law—Assad, in effect, is the law. Due to his undisputed sway over the public sector as the head of state, he has unchecked power to steer and direct state business toward firms he controls through his business fronts. Two examples include Ali Najib Ibrahim and Ramya Hamdan Deeb’s Infinity Skylight, which signed a memorandum of understanding with the Ministry of Electricity for the maintenance and rehabilitation of the Baniyas Thermal Power Plant. They also received a contract to operate the Deir Ali Power Plant near Damascus. Deir Ali’s two power plants are the largest in regime-held Syria and are reportedly being considered for an exemption from Western sanctions so they can be refurbished. Another example is Eloma, which is emerging as the “operator” of Syrian Air. In early 2023, Eloma presented a proposal to the Ministry of Transport to invest $300 million over 20 years to improve Syrian Air’s operations and increase its assets in exchange for a share of its net revenue.

Third, through firms owned by his fronts, Assad is able to wield economic weapons against those deemed potential competitors or challengers, including through the takeover of other firms. For example, LUMA LLC, co-owned by Hamdan Deeb and Ali Najib Ibrahim, now appears as one of the “major shareholders” of Syriatel, once Makhlouf’s crown jewel. While it is not known precisely when the purchase of Syriatel shares happened, it is notable that LUMA was established in July 2021, over a year following the Assad-Makhlouf rupture and subsequent seizure of Makhlouf’s assets in May 2020. The story of Thalj, established in February 2021 and owned by Ali Najib Ibrahim and Ramya Hamdan Deeb, might be similar. Thalj is now listed on the Damascus Stock Exchange as a major shareholder of Al-Aqeelah Takaful Insurance, which Makhlouf and other cronies established back in 2007.

Fourth, Assad’s role as the éminence grise of these networks insulates him from the public scrutiny and criticism that might result from his involvement in corrupt business dealings and in facilitating Iranian participation in Syria’s economy—as reflected in the network map. High-profile regime cronies who display their ostentatious lifestyles on social media are often lightning rods for public anger among Syrians who are struggling to survive. However, even as public anger over the regime’s handling of the economy spreads—sparking recent protests in the regime’s heartland, including Damascus—Assad’s opaque connection to front networks provides him with a layer of protection from the harsh criticism directed toward cronies. It also enables him to sustain his “man of the people” persona—a brand that he and First Lady Asma al-Assad go to considerable lengths to cultivate.

To be sure, the rise of Assad’s front networks carries risks. Not least, while the networks may contribute to the economic resilience of Assad and his innermost circles, they do little to mitigate an economic crisis that has impoverished ordinary Syrians and fuels deep economic grievances that have already sparked significant anti-regime protests. Should the extent of Assad’s front networks become better known, aggrieved Syrians may shift their focus from the government at large to Assad himself. Until now, direct criticism of Assad has been a red line that the public in regime areas has largely observed.

Moreover, Assad’s front networks may also provoke pushback among regime cronies. Thus far, Assad’s fronts have not crowded out the crony networks that still contribute significantly to the regime’s economic resilience, but there is evidence that they are starting to do so. Recognizing that business elites have very limited room to maneuver if they find themselves the “victims” of Assad’s predation, their relationship with Assad may nonetheless become increasingly strained if he expands his pursuit of his personal economic interests at their expense. Should tensions reach this point, business elites may pursue their own strategies of resistance to Assad’s demands, whether by hiding assets, shifting investments abroad, or, potentially, breaking with the regime, the path chosen by established business families such as the Grewatys and Kamel Sabbagh Sharabaty. At present, however, crony networks generate revenues while giving the regime much-needed flexibility in its constant struggle against sanctions.

Assad’s involvement in front networks thus undercuts a widespread narrative in which his distance from economic matters is a source of legitimacy and a basis for elite and public support and loyalty. By contrast, his wife, Asma, is depicted in media accounts as the grasping economic power behind Bashar’s throne. Since Assad’s break with Makhlouf, Asma’s economic ambitions have become both increasingly visible and controversial. She is depicted as moving ruthlessly to consolidate her own Akhras family’s control over peak sectors of the Syrian economy, at the expense of the extended Assad family and of loyalist cronies. However, as indicated by Bashar’s ties to front networks, this characterization rings hollow. Bashar himself is today an important economic actor, and whether emerging front networks are managed by Bashar or Asma has little impact, as long as the fate of the presidential couple is intertwined. Under no circumstances would Asma be able to bypass her husband, even less so given her precarious health.

Finally, and crucially, the front networks that Assad has developed expand his economic room for maneuver. They, together with other tools at his disposal, enable a worldview in which even the appearance of compromise is seen as a signal of weakness that will embolden adversaries. In shoring up the economic bases of Assad’s power, these networks, among other factors, help to explain how, despite Syria’s spiraling economic crisis and the impact of sanctions, the regime is able to sustain a rejectionist, give-no-quarter approach, whether in talks around the terms of normalization with neighbors or in relation to the concessions associated with a political settlement of the Syrian conflict along lines envisioned in U.N. Security Council Resolution 2254. Not even the prospect of desperately needed financial assistance from the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia has been sufficient to persuade Assad to address neighboring states’ concerns about narcotics smuggling and refugee return.

What Assad’s front networks cannot do, however, is compensate for the Syrian economy’s dire condition, overcome what the World Bank has recently described as the “collapse of household welfare,” or temper rising social turmoil and despair among ordinary Syrians. Even as Assad maneuvers to expand his economic reach, the state of Syria’s economy has become the regime’s greatest vulnerability, posing much more potent threats to its political survival than the remnants of the armed opposition in northwest Syria or their Kurdish counterparts in the northeast.

Countering Assad’s economic networks

If U.S. and Western leverage over Assad has always been limited, these front networks’ presence creates new obstacles to progress on issues at the forefront of regional and international agendas, including the regime’s role in the production and smuggling of Captagon, its refusal to create conditions that would permit the safe return of refugees, and its continued rebuff of appeals to provide information about the fate of tens of thousands of missing Syrians detained by the regime. To improve the prospects for positive movement on these or other issues, a first step is to shed light on the economic activities that have flourished in the absence of public knowledge or scrutiny.

If sunlight is the best disinfectant, the Biden administration would be well served by calling out Assad’s front networks. Such an effort is a necessary prerequisite for additional measures to blunt the effectiveness of these networks. Some but not all of the individuals that constitute Assad’s front networks have been sanctioned. Awareness of the firms in which Assad has an indirect stake can assist governments and international organizations to avoid sanctions violations and inadvertently supporting Assad. Donor governments in particular need to ensure that their contributions to U.N. humanitarian operations in Syria are not corrupted by cooperation with regime-linked and sanctioned entities and individuals.

Measures such as the Assad Regime Anti-Normalization Act, which was approved in an overwhelming bipartisan vote in the U.S. House of Representatives but is now languishing in the Senate, include provisions that would empower the Biden administration to raise the visibility of Assad’s front networks, ensure that firms and individuals linked to Assad are sanctioned, constrain his room to maneuver, and raise the costs to Assad of continued intransigence. As shown in the interactive figure above, only one of the front individuals, namely Yasar Ibrahim, is subject to U.S. sanctions. If the United States is serious about its rejection of normalization, focusing its attention on currently unsanctioned regime fronts would send an important signal to Assad and those who are normalizing with his regime that the United States is prepared to take concrete action to constrain Assad’s economic room for maneuver.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

This publication is part of a broader project of the Observatory of Political and Economic Networks (OPEN), co-led by the authors, to investigate the evolution of business networks in Syria during the ongoing conflict. The authors would like to thank the Rockefeller Brothers Fund and the Asfari Foundation and Linkurious for their support of the project. They also thank Jaber al-Kasem and Wael al-Alwani for their contributions to the underlying data, Adam Lammon for editing, and Rachel Slattery for graphic design and layout.

-

Footnotes

- OPEN is a non-profit research organization which focuses on complex networks of power, money, politics, and privilege in Syria. OPEN’s proprietary database maps over 82,000 verified relationships among 51,000 Syrian and non-Syrian actors, including registered businesses, members of parliament, heads of security branches, religious leaders, warlords, civil society organizations, U.N. agencies, crony capitalists, businesspeople, militia leaders, and Syrian army generals.