This week, eight Southeast Asian leaders descend on Washington for a special summit hosted by President Joe Biden. They represent most of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), a diverse grouping ranging from the city state of Singapore to the sprawling archipelago of Indonesia. Taken together, ASEAN’s 10 countries boast a population of over 680 million — more than Latin America, the Middle East, or the European Union — forming the fifth largest economy in the world with a GDP of $3.2 trillion.

In recent years, Southeast Asia has become a focal point of strategic rivalry between China and the United States. Alongside aggressive efforts to enforce its territorial claims in the South China Sea, Beijing is increasingly achieving its strategic goals through economic statecraft. Its signature Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), focusing on infrastructure, and new regional trade agreements like the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) are expected to accelerate intra-Asian integration around China.

The summit will focus heavily on economic issues, reflecting U.S. efforts to meet the China challenge and expand economic engagement with the region. Biden is also expected to push ASEAN leaders to adopt more critical stances toward Russia over its invasion of Ukraine. On the first day of the summit, they will meet with congressional leaders, Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo, and Trade Representative Katherine Tai, followed by a White House dinner hosted by President Biden. The summit will move to the State Department on the second day, with discussions focusing on infrastructure, supply chain resilience, climate change, and sustainability, ending with a plenary session with Biden. Climate challenges resonate strongly in Southeast Asia, a maritime region particularly vulnerable to rising sea levels and severe weather events.

The gathering presents an opportunity to take stock of U.S.-ASEAN relations in the Biden administration’s second year. What has emerged, it seems, is a convergence of unrealistic expectations, with both sides wanting what the other is incapable of delivering. For ASEAN, which wants to reduce its economic dependence on China, the hope is that Washington will commit to a regional economic strategy that includes binding trade commitments and eventually a return to what is now the 11-member Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). But expanding market access is a political non-starter for Biden, with Trump-era protectionist sentiment still running high among key segments of the American electorate. For Washington, the hope is that ASEAN will stand up to Chinese aggression or at least voice support for a rules-based order that constrains Chinese behavior. But this is a non-starter for ASEAN, which is internally divided and does not want to take sides between Washington and Beijing.

the Biden administration’s engagement with ASEAN

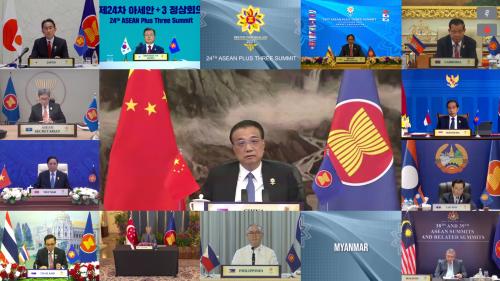

Last year, the Biden team got off to a slow start with ASEAN, but engagement picked up in the second half of the year with a series of high-level visits to the region by Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin, Vice President Kamala Harris, and Secretary of State Antony Blinken. President Biden virtually attended the annual U.S.-ASEAN Summit, which occurs alongside the ASEAN Summit and East Asia Summit each fall. “I want you all to hear directly from me the importance the United States places on our relationship with ASEAN,” he told the grouping. Biden also underscored the U.S. commitment to ASEAN “centrality,” the notion that ASEAN provides the central platform within which regional institutions are anchored.

During this period, a key theme of the administration’s messaging to ASEAN was that Washington was not asking the region to choose between the U.S. and China, but rather trying to ensure that Southeast Asian countries have choices. This theme was apparent when Blinken previewed the administration’s emerging Indo-Pacific strategy in a speech in Jakarta. He strongly criticized China, slamming “aggressive actions” in the South China Sea and economic practices “distorting open markets through subsidies to its state-run companies.” However, he also said the goal is “not to keep any country down,” but to “protect the right of all countries to choose their own path, free from coercion, free from intimidation.”

The new messaging and stepped-up engagement were appreciated in the region. However, as “strategic competition” was clearly hardening as the new paradigm in U.S.-China relations, anxiety over the inevitability and perils of a binary choice seemed to increase among Southeast Asians.

The basic content of Blinken’s speech was formalized as policy when the White House released its “Indo-Pacific Strategy” in February 2022. A key theme is that the goal of creating a free and open, connected, prosperous, secure, and resilient Indo-Pacific cannot be achieved with Washington acting alone. Rather, historic challenges and the shifting strategic landscape “require unprecedented cooperation with those who share in this vision.” To this end, the U.S. will “deepen long-standing cooperation with ASEAN” and engage on climate and other pressing issues, while exploring “opportunities for the Quad to work with ASEAN.”

This reference to the Australia-India-Japan-U.S. quadrilateral grouping is related to parallel efforts by the administration to expand the Quad’s focus beyond security to include a new vaccine partnership as well as working groups on climate change and emerging technologies. Southeast Asia has been suspicious of the Quad, seeing it as a challenge to ASEAN centrality. In this new framing, however, the Quad could become a source of public goods for Southeast Asia rather than a competitor in Asia’s dense patchwork of regional institutions.

In October, Biden also announced plans for a U.S.-led Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF). The framework, which could be launched this month, will allow countries to sign up for “different modules covering fair and resilient trade, supply chain resilience, infrastructure and decarbonization, and tax and anticorruption.”

The Regional response

The administration’s approach to Southeast Asia appears to have resulted in some near-term dividends. In a regional survey conducted in November and December among policy experts across ASEAN, the level of trust in the United States increased to 52.8% from 47.0% the previous year. 58.5% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that the strengthening of the Quad, including through practical cooperation, would be constructive for the region.

On the other hand, only 45.8% of respondents perceived that U.S. engagement with Southeast Asia had increased under Biden, a decrease from the previous year’s expectations. On the Lowy Institute’s latest Asia Power Index, the U.S. registered a 10.7-point decline in economic relationships even though it gained significantly in diplomatic influence. Meanwhile, there has been little reaction from ASEAN to the Indo-Pacific Strategy. Although this may be due to the timing of its release just before Russia invaded Ukraine, it is also because ASEAN countries prioritize economic issues. They have been largely focused on IPEF, but the framework’s regional reception has been lukewarm owing to the focus on standard setting rather than market liberalization.

Regional views are mixed on the Russia-Ukraine war as well. Only Singapore has sanctioned Russia. Indonesia, Brunei, and the Philippines condemned the invasion without identifying Russia as the aggressor; Vietnam and Laos abstained from the March 2 United Nations General Assembly vote condemning Russia’s aggression; and Myanmar’s military rulers vocally supported the invasion. Singaporean ambassador-at-large Chan Heng Chee says the varied response shows that ASEAN countries are seeking a “third space” in their diplomacy as they strive to avoid taking sides between U.S.-led critics of the invasion and the Russia-friendly camp exemplified by China. This response is seen in the decision of Indonesian President Joko Widodo to invite Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy to attend the G-20 summit in Bali in November while resisting Western pressure to exclude Russian President Vladimir Putin.

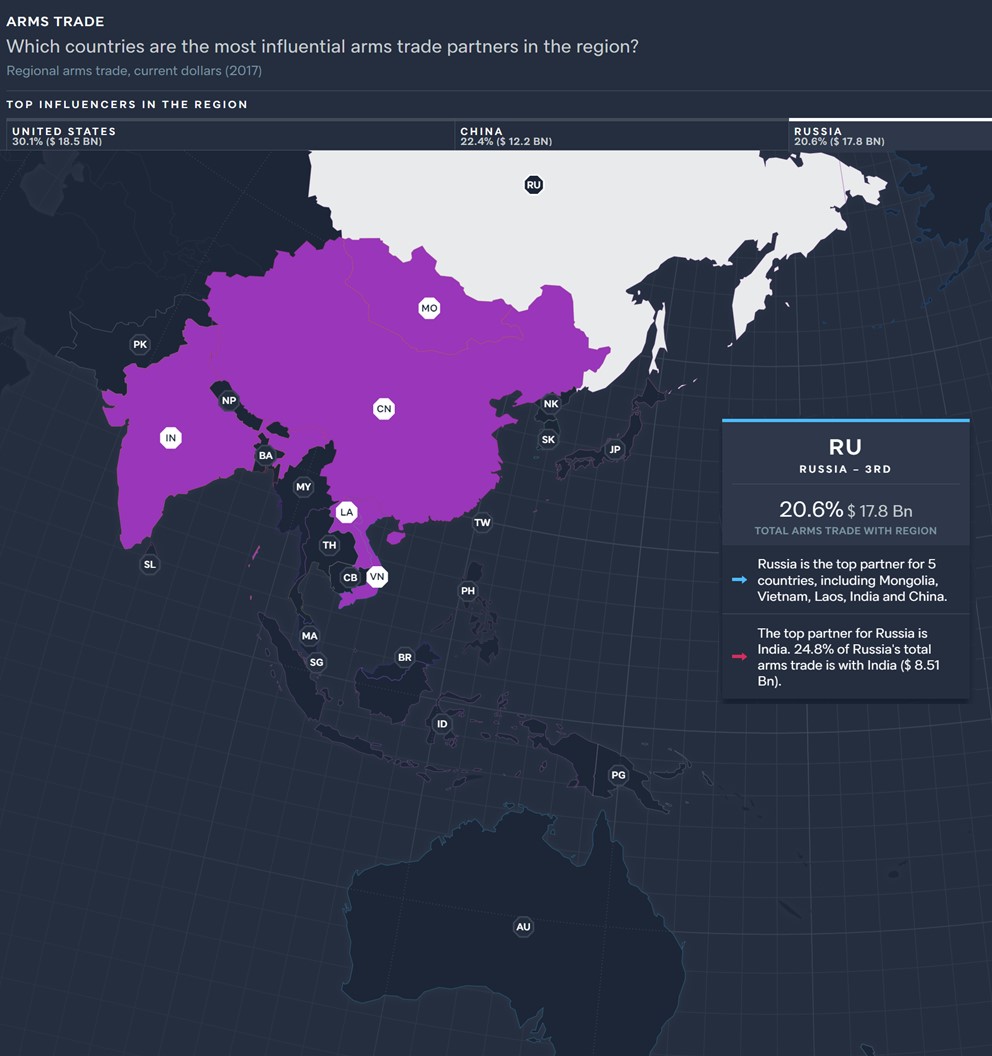

Russian arms exports no doubt shape some states’ interests. As depicted in the figure below, drawn from the Lowy Institute’s Asia Power Index, Russia is the top arms supplier for Vietnam and Laos — as well as India.

Cognizant of these divisions and sensitivities about the Quad, the Biden administration has been responsive to ASEAN demands to respect “ASEAN centrality,” partly in the hope that the grouping can effectively address difficult regional issues like the deteriorating political and humanitarian situation in Myanmar. Diverging strategic outlooks among ASEAN’s membership, which grew from five countries at its inception in 1967 to 10 by the end of the 1990s, are understandable. Yet, constant ASEAN assertions of its “centrality” appear increasingly defensive to those outside the region, exposing insecurity rather than a sense of community and confidence. Southeast Asian foreign policy experts have themselves been voicing growing concerns, saying ASEAN is confronting the gravest institutional crisis in its history. ASEAN centrality cannot just be claimed, they argue; it has to be earned.

The summit and beyond

It is against this backdrop that the special summit convenes, no doubt shaping what is included (or not) in the outcome document on such issues as Myanmar, Ukraine, and trade. Regional observers will be watching to see if the document establishes a firm timetable for upgrading ASEAN’s relationship with the U.S. to a “comprehensive strategic partnership,” as with China and Australia last year. Meanwhile, the administration is planning to roll out a number of initiatives at the summit. It could also instill confidence by announcing new diplomatic appointments to the region, especially for the long-vacant ambassadorship to ASEAN itself.

Looking further ahead, it behooves the United States and ASEAN to approach their relationship through a prism of creative realism, understanding constraints on both sides but also opportunities — not least a joint concern for climate change and sustainable development in the years ahead. Doubling down on the U.S.-ASEAN Climate Futures initiative, announced in October 2021, would be a good place to start.

Commentary

Taking stock of US-ASEAN relations as Biden convenes a special summit

May 11, 2022